King’s Lynn – St James Chapel

There’s not much left of St James Chapel and what remains isn’t accessible to the public, although at least the burial ground sort of survives. It was though once a substantial building and it was founded at the same time as the Chapel of St. Nicholas. It’s known as a chapel rather than a church, as it was intended to be used as a chapel of ease to the Church of St. Margaret. Work started on the chapel in the twelfth century, but because it was a chapel at ease, there isn’t a huge documented record from the medieval period.

As an aside, there was a man named William Sawtrey, who caused a considerable scene in the late fourteenth century by espousing Lollard views. They were early reformers and caused something of a threat to the Catholic Church, which meant that the authorities in Norfolk wanted to stamp down on this rebellion (and there’s a pub called Lollard’s Pit in Norwich which is located by a place where many of these reformers were burned at the stake).

Anyway, Sawtrey rejected Catholic saints, opposed pilgrimages and didn’t want images to be venerated. This was a bit of a problem for the church as Sawtrey was the priest at St. Margaret’s Church in King’s Lynn, so Henry le Despenser was called in as he was the Bishop of Norwich. Despenser was not really the kindest of men, he put down the Peasant’s Revolt in Norfolk in a bloody style, he maintained privilege and he also tried to destroy those who wanted reform of the Catholic Church. He is buried in front of the high altar of Norwich Cathedral, which might annoy him since the protestant reforms he fought against eventually took place and his body is now left in a Church of England building.

I digress though. Despenser sent Sawtrey to prison, but he was released as long as he condemned the Lollard movement and he had to do this in front of the Chapel of St. James (which is why I’m telling this convoluted story….). Sawtrey apologised to God in the churchyard of the chapel on 25 May 1399 and he promised Despenser that he would never again challenge the authority of the Catholic Church. To cut another long story short, Sawtrey just went to London instead to preach his Lollard views and he was executed in March 1401.

Moving forwards to the Dissolution of the Monasteries though, as this period was well recorded, and the Reformation had a large impact on the town of King’s Lynn, not least as it had been known as Bishop’s Lynn, but also as numerous monasteries and religious institutions were closed down, including this chapel.

On 17 December 1544, the plate belonging to the chapel of St. James was flogged off and the money was used to strengthen the town walls against the threats of the sea. On 2 February 1548, the authorities announced that the building would be taken down and the bells were sold in 1550, with the money being used to buy ordinance and artillery to defend the town. Work started to take down the stone, wood and lead, but it was agreed locally that the chancel area would remain standing and would be covered in tiles.

In 1560, the Lords of the Council came to have a little look at what arrangements were taking place in Lynn with regards to the chapel. Probably not very efficient ones, as the town corporation got quite grumpy at this situation and told them to clear off. Work continued slowly and in 1568 it was decided that the wealthy Duke of Norfolk could have 20 loads of freestone if he wanted it, and because he was so wealthy, the corporation wouldn’t charge him for that. Nothing really changes….

A fair sum of money was spent on turning the building into a workhouse, which opened on (or was decided on) 1 June 1582, a purpose which the site was to retain for a few hundred years. In 1597, when the plague hit King’s Lynn, it was also the location where the ill were sent, perhaps with not much concern for those already in the workhouse.

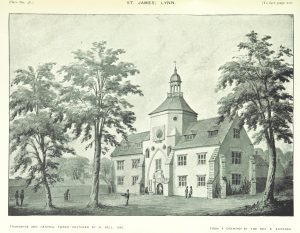

In the 1680s, what remained of the medieval structure was turned into a new workhouse building which was designed by Henry Bell, and it’s this that can be seen in the above image. Between 1805 and around the 1870s, the area near to the chapel was brought back into use as a burial ground, but the gravestones were collected together in 1903 and the space was turned into a park.

The central bay and the tower of this building collapsed in August 1854, which wasn’t entirely ideal. The incident came to the attention of the national media and it was reported that:

“About half past 11, the whole central tower came down with a tremendous crash, distinctly heard throughout the town. Scores of labourers at once set to work clearing away the debris as far as possible, in order to extricate those who might be below, it having been reported that many people had been killed. Fortunately, however, this turned out to be incorrect. The girls were at church at the time and the boys sitting in front of the building, to the right of the tower. A few minutes before the building fell in, Mr. Nelson, the governor of the workhouse, attended by Mr Andrews, went to the clock room to see what was amiss. Whilst they were there the fall took place, and they were carried down amidst an immense mass of material. These two gentlemen, it was concluded, were inevitably killed, with several old men who could not be found. The escape of several of the inmates was almost miraculous”.

There’s a story about someone kicking the clock which caused the whole structure to fall down, but none of the press at the time seemed to mention that, so I’m not sure where that information comes from. Other reports note that just one elderly man died, which was primarily as he refused to get out of bed. A new workhouse had to be constructed quickly and this opened on Extons Road in 1856.

What was left of the structure was mostly demolished in 1910, with just a small section now remaining. The central part of the remaining structure with the bricks and large window is from the sixteenth century, with the medieval stone of the earlier chapel being visible on either side of that.